Size labels are meant to simplify buying clothes.

In practice, they often do the opposite for the plus size bodies.

Many people wear the same labeled size across multiple brands — yet experience repeated fit failures in specific places: the bust, the waist, or the hips. The garment may technically be “their size,” but still pull, ride up, gap, roll, or collapse in motion.

The assumption built into size labels

Most clothes are designed using proportional size rules.

That means when a size increases, the pattern assumes the body expands evenly:

- bust, waist, and hips all grow together

- depth and width increase at the same rate

- vertical proportions remain stable

Real bodies rarely follow this model — especially in plus-size ranges.Instead, fullness tends to concentrate in specific zones, not everywhere at once. Some of us have fuller bust, some fuller behind, some larger waist. After all, this is why there are defined body shapes.

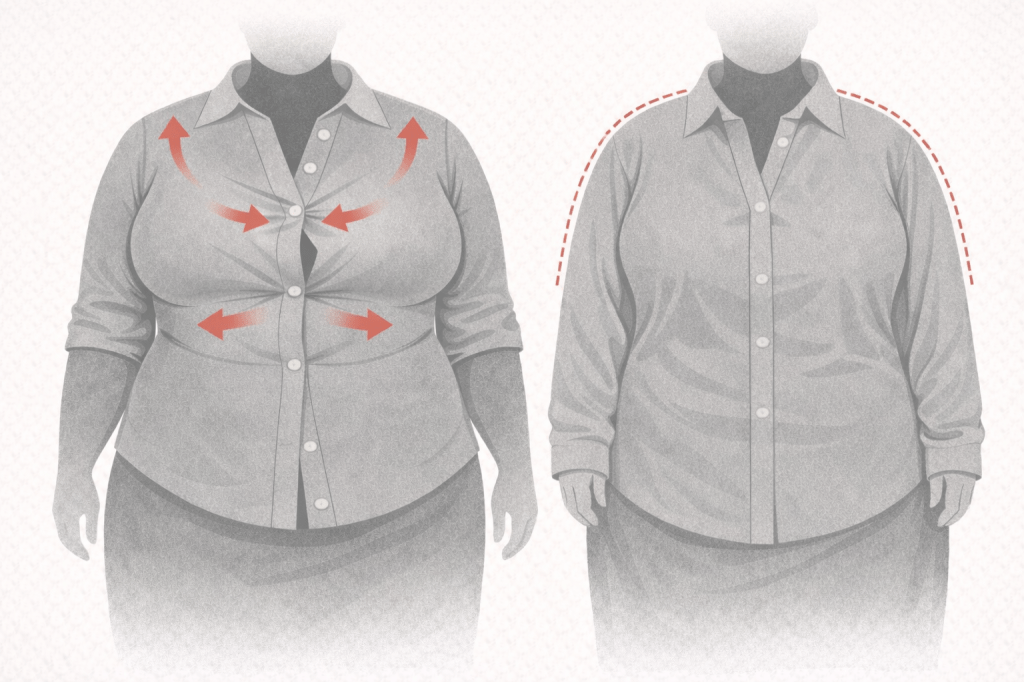

Bust-dominant bodies

When most volume sits in the bust:

- fabric is pulled upward and forward

- waist seams rise and lose position

- armholes distort or dig in

- buttons gap despite correct sizing

The issue isn’t “too small.”

It’s upward tension caused by insufficient bust depth.

The garment doesn’t have enough room in front, so the fabric gets pulled from other places instead. And when it does, then oversized shoulders or sleeves are too long.

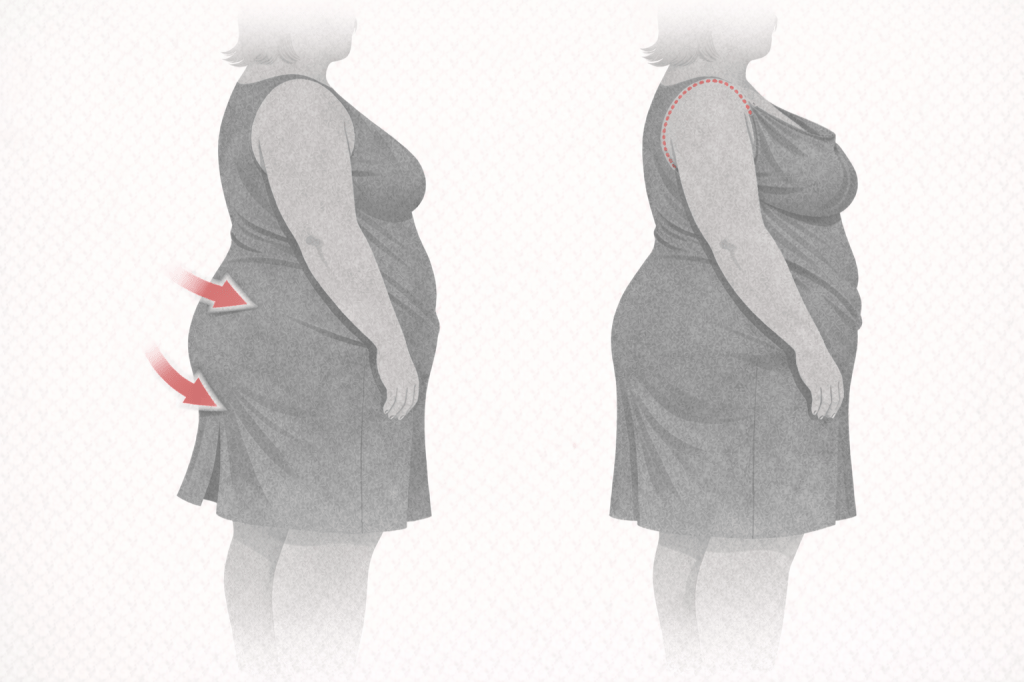

Waist-dominant or abdominal fullness

When volume is concentrated at the midsection:

- waistbands roll or cut in

- dresses collapse forward

- fabric clings when sitting but loosens when standing

This happens because many garments rely on horizontal compression at the waist. Bodies move and shift. Many garments don’t.

The result is a garment that fits briefly — then fails in motion.

Hip- or seat-dominant bodies

When volume is concentrated at the hips or seat:

- skirts ride up in the back

- hems become uneven

- side seams pull backward

- fabric strains over the rear while appearing loose elsewhere

Most patterns assume a flatter seat than many real bodies have. When back rise or depth is under-built, the garment is pulled backward and upward, even in the correct labeled size.

The problem isn’t the body. It’s that the garment isn’t built to carry the load.

What matters more than the size label

Fit reliability depends less on the number on the tag and more on how a garment is constructed.

Consistently important factors include:

- seam placement and direction

- allowance for depth (bust, seat, or abdomen)

- fabric recovery after stretch

- how tension is distributed when the body moves

A well-constructed garment in the “wrong” size often performs better than a poorly constructed garment in the “right” one.

How to use this information

When trying on clothes, stop asking “Is this my size?” and start asking:

- Where is the fabric under the most tension?

- Does the garment allow depth where my body needs it most?

- Does it still work when I sit, bend, or walk?

If a piece consistently fails in the same area, the issue is likely structural — not personal.

That knowledge alone can save time, money, and frustration.